Dismantling the Myth of “Mad Genius”

The problematic, age-old trope of the “tortured” or “mad” creative genius goes back years and years, from the days of Van Gogh and Monet, and persists today, through the example of more recent pop cultural figures such as Alexander McQueen or Anthony Bourdain, whose mental health struggles and eventual ends were well-documented by the media. Could these individual instances be indicative of a highly creative mind, or of a wider societal problem? Research studies would indicate both. We recommend two recent articles on this topic.

The first, from Business Insider, provides a useful overview of research on the link between creativity and mental illness. Among the cited studies, one conducted from 2011 to 2015, by the Office of National Statistics in England, found that people working in an arts-related field were four times as likely to commit suicide; while a 40-year total populations study, published in the Journal of Psychological Research in 2013, found that patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, among other mental health illnesses, are “overrepresented in creative occupations.” Additional studies also show that people with high intelligence are likely to be night owls, are more creative, and can sustain mental alertness for a longer portion of the day than early risers. And being morning or evening-oriented has more to do with genetics than choice, with a group of brain cells marking individual preferences for our internal clocks.

Woman falling through the cracks. Image by Supriya Bhonsle via mixkit

Correlation does not necessitate causation, however, and while these studies clearly demonstrate the links between mental health and creativity, many skeptical psychologists argue that “people with emotional volatility might be drawn into creative industries and the entertainment world,” which come along, of course, with a watchful public eye. But if we can understand the significance of these studies, arts and cultural institutions ought to extend and demonstrate a level of care and responsibility for its visitors and local community—and clearly prioritize the budget for such initiatives, which are often the first to go in times of financial duress. But mental health is a growing epidemic in the United States, where one in five people experience mental illness, and urgently demands the attention of many organizations. Museums might look to examples in other sectors for case studies on how to actively address this issue, and in particular, college campuses, which disproportionately face mental health hardships. Suicidal thinking, depression, and self-injury among U.S. college students have doubled in the past decadean alarming rate that has likely compounded in recent months, due to sudden COVID-19 related closures.

Happiness lies in healthy habits, rather than achievements. The journey towards a happier self is a life-long pursuit that requires not just awareness, but practice.

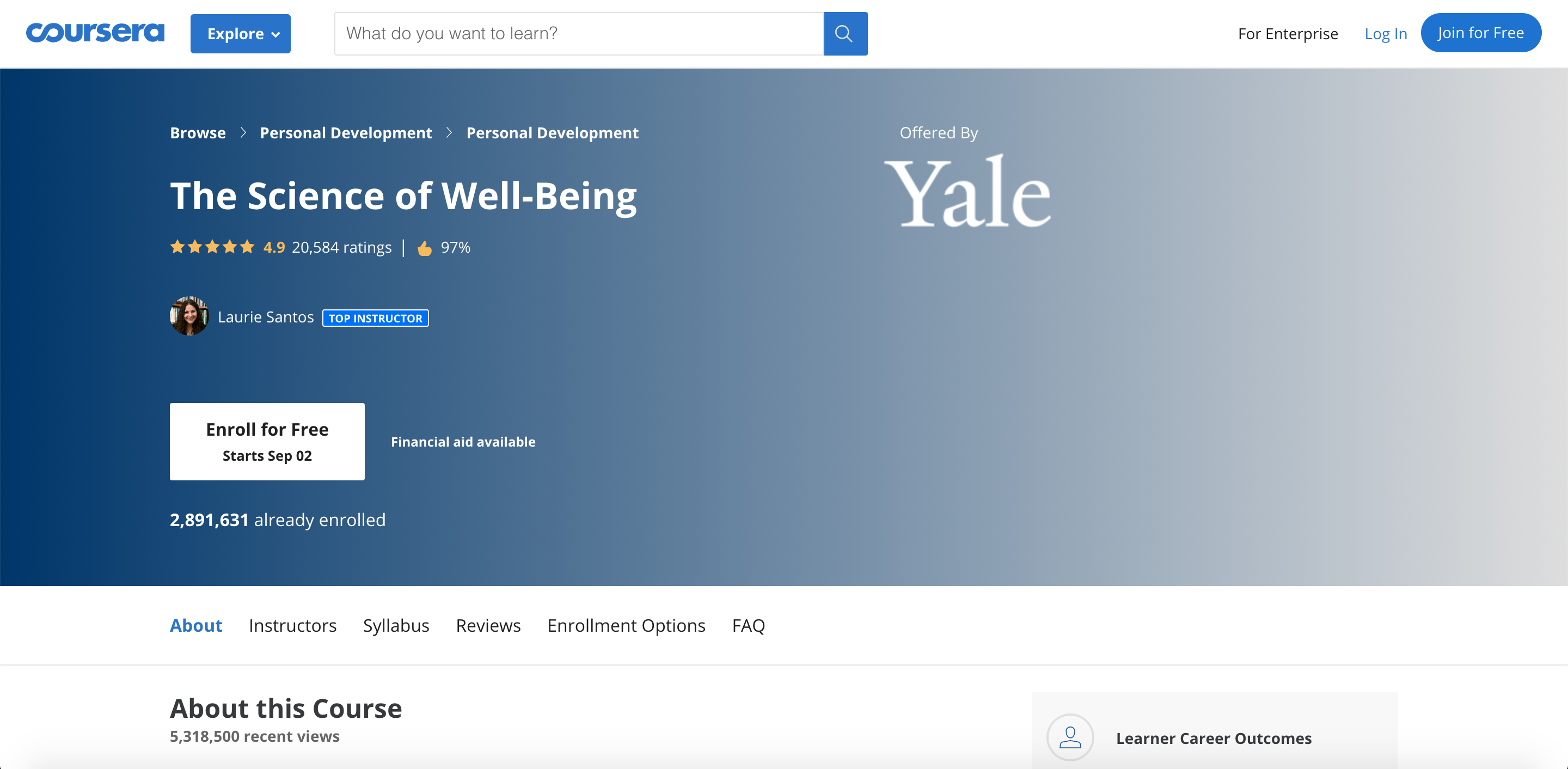

We recommend this recent story from The Cut, which demonstrates how an experimental course at Yale University has reverberated to wider societal benefit and resources for the public. First, some useful context: In 2018, Yale psychology professor Laurie Santos launched a seminar “Psychology and the Good Life,” commonly referred to as the “Happiness” class, after feeling a “shock at the kind of mental health issues” she observed, as the head of a residential college living among students on campus. The course quickly became the most enrolled course in the University’s history, and was so well-received by students that Santos launched a second iteration, re-titled “The Science of Well-Being,” on the online educational platform Coursera, available for public auditing, free of charge. In his story for The Cut, writer Adam Sternbergh inspected the buzz around Santos’ public Coursera offering by signing up for it himself—then detailing the experience. The first session prompts participants to take a “happiness quiz” to assess a starting point for each student, and his initial hesitation to do so reveals a telling stigma: “I’m a little scared to pop that illusion for myself. How happy am I, anyway? And do I really want to know quantitatively?” But as Santos reveals, her Yale students were less worried about what they learned about themselves—and more about the possibility of receiving a poor grade, when she joked she would assign a D to most students, on the basis that “high achievement and good grades don’t lead to sustained well-being.”

The Science of Well-Being course on Coursera, Image via coursera.com

For those interested but hesitant to take the leap, Sternbergh’s recap is a helpful preview into all 20 lectures. By the end, he shares his final happiness score, of 3.79 out of 5, which places him in the 80th percentile of happiness for people in his age, gender, and zip code. “There’s room for improvement, and, thanks to this course and the research it draws on, I have lots of ideas of how to go about it. This afternoon, for example, I’m going to cancel an appointment and do something pointless for an hour,” he writes. “The first lesson of ‘Psychology and the Good Life’ is that happiness is something worth working at. The final lesson is that the class never truly ends. But for now, as scores go, I’m pretty happy with it.” The main takeaway from Santos’ course, backed by neuroscience research, is deceptively simple: Happiness lies in healthy habits, rather than achievements. The journey towards a happier self is a life-long pursuit that requires not just awareness, but practice.

Sternbergh’s satisfaction with the course largely mirrors that of most participants. To date, the course remains among Coursera’s most subscribed, counting nearly 3 million enrollments, with 35% of learners reporting that completing the course has led them to embarking on a new career path. These outcomes demonstrate that people have a real need and enthusiastic interest in learning how to manage and improve their wellbeing, are willing to invest time and effort into it, as well as challenge taboos about confronting mental illness in a novel context and setting.

Museums, too, have an opportunity to take a more active role in examining the role of mental health and creativity, and demonstrate that this conversation absolutely has a place in our cultural institutions. Acknowledging these links without addressing them not only fetishizes and perpetuates the trope of the “starving artist” or “mad genius”—it flattens and erases the human aspect of creative labor, and the societal and psychological hurdles that individuals often endure for the sake of their art. Through a mix of educational and instructional workshops oriented around creativity and wellbeing, they can begin to embrace mental health to foster a well-balanced outlook that takes an honest look at the human mind within the context of creativity.

If you or someone you know is struggling with depression or has had thoughts of harming themselves or taking their own life, get help. The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (1-800-273-8255) provides 24/7, free, confidential support for people in distress, as well as best practices for professionals and resources to aid in prevention and crisis situations.

Aileen Kwun is a writer, editor, producer, and consultant with an expertise in design and culture. She contributes to publications internationally and was a senior editor at Dwell and Surface, as well as a founding member of Superscript and a strategist at Project Projects. Her first book, Twenty Over Eighty: Conversations on a Lifetime in Architecture and Design, was published by Princeton Architectural Press. Aileen holds degrees from UC Berkeley, the Columbia Publishing Course, and the School of Visual Arts.