“The Rise of Messy, Inconsistent, and Emerging Architecture”

One of my first jobs was for an architect who loved to flaunt his knowledge of, and fascination with, the golden ratio. Used by many of the greats in the centuries before him, I often felt it must have been his way of claiming territory among their greatness. The golden ratio embodies a perfect proportion between different quantities. It can be found across the arts from music to art to architecture, with a basis in mathematics and nature.

It must indicate changing times that this architect still has not received his now long-awaited Pritzker prize. The focus of the jury, in recent years, has started shifting to different types of architecture. It shows that the perfection of form and space still celebrated by some of the older generation’s architects may not be the type of architectural perfection we need for the future. Their drive to find a sense of harmony and balance still holds, but how this manifests needs to shift drastically.

Perfection in architecture has had many expressions over time, ranging from grand feats of engineering, to impeccable details in understated modernism, and countless identities of the iconic. It would often go hand in hand with the notion of the genius architect or, as one would now think, with often unnecessary intellectual elitism. In all its expressions, quests for perfection have been a major driver behind many designs for cultural institutions worldwide. And, too often, we would forget that a building, so seemingly perfect at its time of completion, would prove less perfect for future generations.

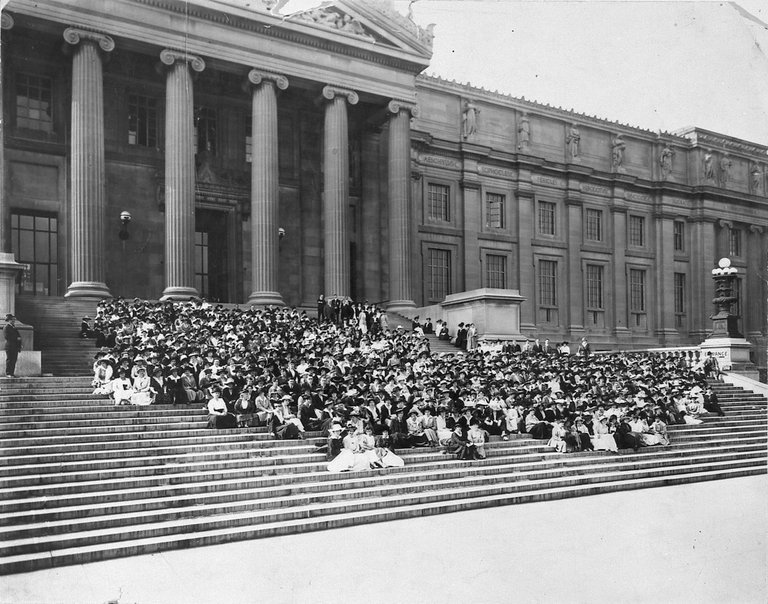

Brooklyn Museum: exterior. View of the Grand Staircase and West Wing from base of the staircase, showing teachers from District 33 and 34 sitting on the Grand Staircase during sessions of the Teachers’ Institute, 09/11/1916.”, 1916. Bw negative 4x5in. Brooklyn Museum, Museum building.

The Brooklyn Museum is a good example of how different times require different solutions. When it was first built in 1895 by McKim, Mead & White, the museum had a grand staircase similar to that of the Metropolitan Museum. If you show people photos of it now, they consistently reference the Metropolitan. Not surprisingly, there are few still alive who remember that staircase. Under William H. Fox’s leadership in 1929, the imposing staircase gave way to a series of doors placed right at ground level. It is comical to see it then reappear again in the Polshek renovation, yet still with its main entrance at ground level. Times change.

To me, perfection in institutional architecture these days is not found in yet another grand museum building or fancy concert hall. To me, it is found in messiness, temporality, and flexibility. Each embracing imperfection in different ways, this type of perfection is driven by a desire to connect with people, follow or shape their behavior, celebrate human energy, and allow for changing programs. It best manifests itself in the adaptive reuse of former industrial buildings, mobile pavilions, and temporary interventions.

Overlapping programs at the BMW Guggenheim Lab

Overlapping programs at the BMW Guggenheim Lab

Ten years ago, I dreamed of getting everyday people to think about their lives in cities differently and to give people the data needed for them to feel sufficient agency to show up in community board meetings and participate in local elections. It was important not to speak to them from the pedestals of institutions, but to meet people in cities, on the street, and to listen, and to talk—together. Together with Maria Nicanor, I developed the BMW Guggenheim Lab, an urban think tank that traveled around the world in its own building, welcoming everyday urbanites to create and participate in public programs, experiments, games, and to just be. The project was intentionally open-ended and undefined—leaving both the Guggenheim and BMW scratching their heads, confused as to how to push us toward more immediate and measurable key performance indicators, a term I still loath.

At that point, it was, to me, mostly about the program and getting people to examine their relationships with cities. Now, I can see that it was the beginnings of a different philosophy around institutions and institutional architecture. Far away from the white box (or spiral, in our case), the project was located in a small mobile box-like structure that would hover over urban spaces and turn them into the podium for that neighborhood. Its fly-house mechanism created a light-hearted open-air operatic urban backdrop to which everyday urbanites suddenly played the first violin.

If we created it today, we would think more about long-term relationships with the communities we frequented and aim for even greater diversity among its participants. Still, in many ways, the project was both of and ahead of its time. Of course, the project had to take place in an environment that was layered, an environment in which it was not clear where one program would end and the next would start, both in time and space.

Guggenheim BMW Lab

Guggenheim BMW Lab

Working closely with Atelier Bow-Wow, Japanese architects with a knack for perfecting quirkiness and wabi-sabi (the art of embracing imperfection), we created a space that, at any time, was messy and playful but that carried a deep sense of that harmony and balance. Here, it was not so much found in the Lab’s façade or form, but it lingered between its space and its users. To us, even a protest against the lab as gentrifying entity staged by neighborhood activists in the actual lab space, felt inexplicably part of the program even though it must have left museum management and the related PR machines tangled and troubled.

For a moment this morning, when I started writing, I thought architecture had come a long way since then. I decided to do a quick search to kick-start my creative juices, and I thought to have hit the jackpot when Google almost immediately answered my search for messy architecture with articles about “agile architecture, the rise of messy, inconsistent, and emergent architecture” and with articles starting with “the need for reinventing how we think about and approach architecture is becoming ever more prevalent, especially if an organization is to truly become agile.”

That we still have a long way to go in letting go of perfection in architecture in favor of forefronting people and their needs—especially for cultural institutions—became clear to me when all those search results turned out to be referring to IT architecture instead.

David van der Leer, Principal of DVDL, is a consultant, educator, moderator, researcher, strategist, and writer. David’s passion is reinventing the institutions of yesterday—and dreaming up the most inspirational institutions of tomorrow—through excellent architecture and interdisciplinary programs. David founded DVDL in 2018 after having worked and consulted with institutions, government agencies, corporations, and individuals for 15 years. He has extensive experience in bringing together interdisciplinary teams to create successful design projects. David teaches a course called (Re)Programming Museums at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture Planning and Preservation.

David has created, chaired, and led nearly 30 design competitions, and he has commissioned numerous design and art projects. He enjoys rethinking conventional design competition and commissioning processes, and actively promotes new practices in events like the Design Competition Conference he developed and co-chaired at Harvard University in 2015. Born and raised in The Netherlands, David is a graduate of Erasmus University Rotterdam, and of the High Impact Leadership program at Columbia University’s Business School.