Mindy Fullilove, Social Psychiatrist

DL: Can you, as a social psychiatrist, help us understand the difference between mental health and mental illness?

MF: I think it is important to say that mental illness and mental health are not the same thing. As a psychiatrist, mental illness concerns the disorders—like schizophrenia or posttraumatic stress disorder—that interfere with mental functioning. Mental health is the ability of individuals to function creatively and lovingly in the world, realizing their abilities and dreams in their work and play.

As a social psychiatrist, my work is concerned with mental health. I see strong social bonds as the foundation for mental health. I look at how we create the conditions for mental health, for people to work together, for individuals to function, and for the whole group to be able to solve problems. Social bonds allow the group to acknowledge and carry out responsibilities—for example: to care for the vulnerable, to set rules about how people are going to behave, or to support people’s achievements so that they can recognize their own strivings as well as collective strivings, and to be able to name and solve problems.

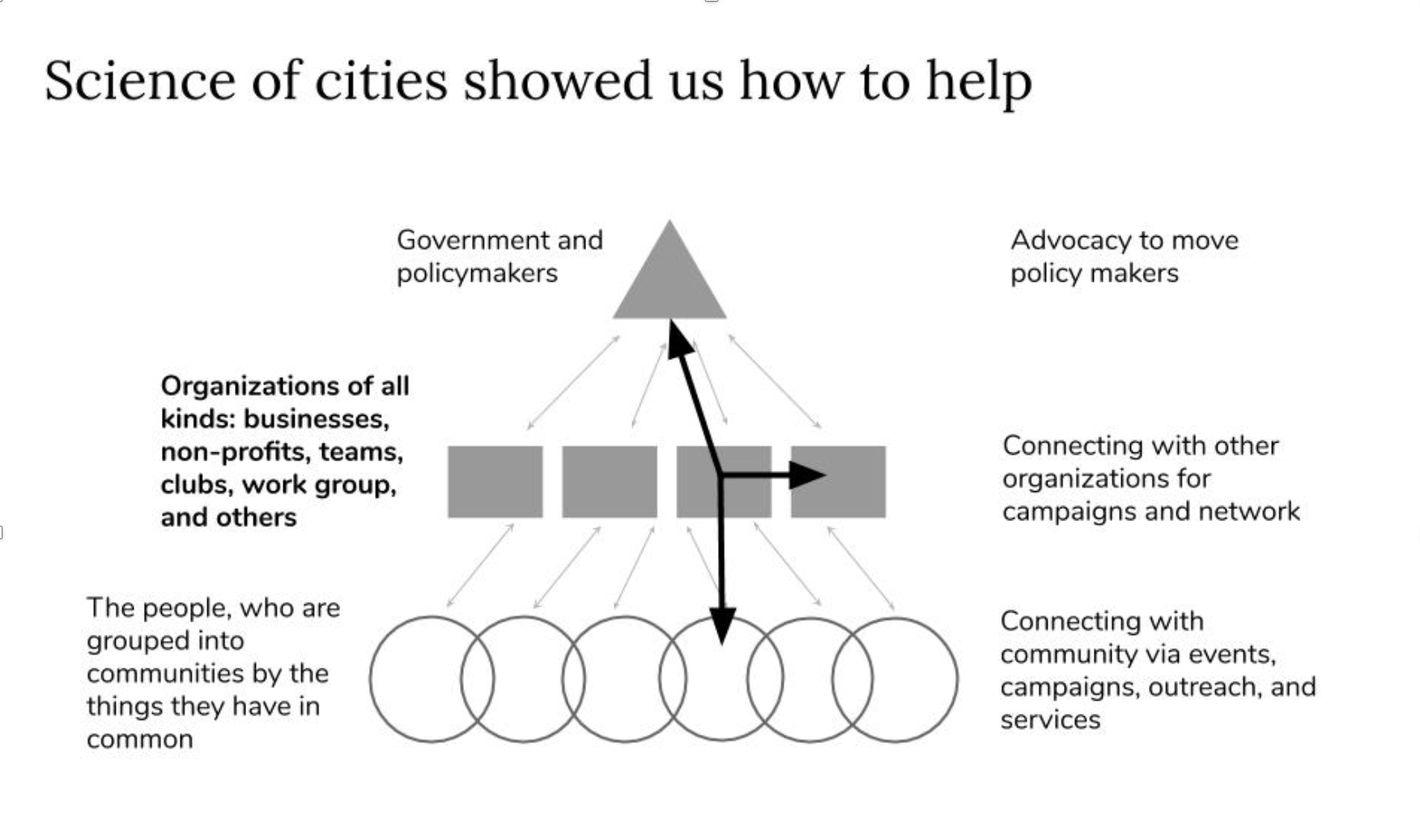

Diagram of the ways in which organizations of all kinds work in the City. Image Courtesy of Mindy Fullilove.

DL: What is happening to our mental health right now?

MF: People are having a lot of mental health symptoms right now, but these symptoms are normal in a disaster. It’s very unstable. It’s very frightening. You’re supposed to be frightened. People are dying. You’re supposed to be sad. The government is terrible. You’re supposed to be reacting. We’re supposed to be in sync with the world. Our emotions are supposed to reflect what’s going on. It doesn’t mean that there’s mental illness. It means people are in a very difficult situation.

We have been a very sick society for a long time, and got sick because we enacted many decades of policies that destroyed these social bonds.

DL: Is this just about COVID-19?

MF: No, we’re in a profound crisis all around, and this is the free fall. You can’t do things to a society like mismanage a pandemic, unleash toxic racist attacks every day, and refuse to deal with climate change, and expect to have any sane society left.

But we have been a very sick society for a long time, and got sick because we enacted many decades of policies that destroyed these social bonds. The connections that allowed people to negotiate the differences have simply been demolished. Americans used to read the same books. In fact, when I was growing up, everybody sang the same songs. We don’t anymore. We used to have a common set of metaphors that you could use, which doesn’t exist anymore. When you tear apart society, people are left as individual atoms, and that’s not a healthy state. That is not a society with sound mental health.

DL: What is the role cultural institutions can play to support societal mental health at this time?

MF: As a social psychiatrist, I approach this moment as a time for supporting the mental health of all of us, what we call “collective recovery.”

Achieving collective recovery and restoring mental health, in this moment, means working on safety and stability. Institutions are in a position—and have access to resources—that can get us through this crisis. Every institution and organization, in my opinion, would do well to say, “How do we stop this free fall?” You know when you’re riding your bike and the brakes fail and you have to put your feet on the ground to stop? It’s like that. Organizations have to put their feet on the ground to stabilize us. They can put a foundation under us so we can catch our breath, and not be in free fall. It’s like that bouncy thing that stunt actors land in. We’ve got to make the bouncy thing. Institutions and organizations can do this by focusing on four tasks: Remember, Respect, Learn, and Connect.

Cityscape Town Buildings Nantes City, France; Image via WikiCommons

DL: Have you seen cultural institutions do this successfully in the past?

MF: I have seen a number of powerful examples. In the city of Nantes (France), for example, there was an outcry over a racist attack back in the 90s. The people of the city decided to confront the local roots of racism, which lay in their history as a major port in the slave trade. They dedicated substantial space in their city museum to telling that story. The museum had remarkable artifacts in its archives, including a watercolor of a slave ship detailing the costs of the expedition and the profits it made. These have been put on display. The museum’s work helped to create a new conversation and social consciousness, leading to better mental health in that city. It is an important example of an institution working on RESPECT.

DL: What do you want museums to help us Remember?

MF: Like the museum in Nantes, museums have a lot in their archives. The world has fallen apart before. We have to think about what they can share with us. Museums have to tell us some stories that could get us through this crisis. People need images of solidarity. What if they said together: “We’re going to do a place-based story of solidarity. What’s a story in this city that teaches us how people in the past have worked together to solve a crisis, to get through a crisis?”

What if they said, “October 25th is solidarity day,” and every museum did something that day, so we go into the election with a set of stories about solidarity, as opposed to what we’re going into November 3rd with, which is polarization. That’s the kind of thing that can move a whole society. That would be a real mental health intervention.

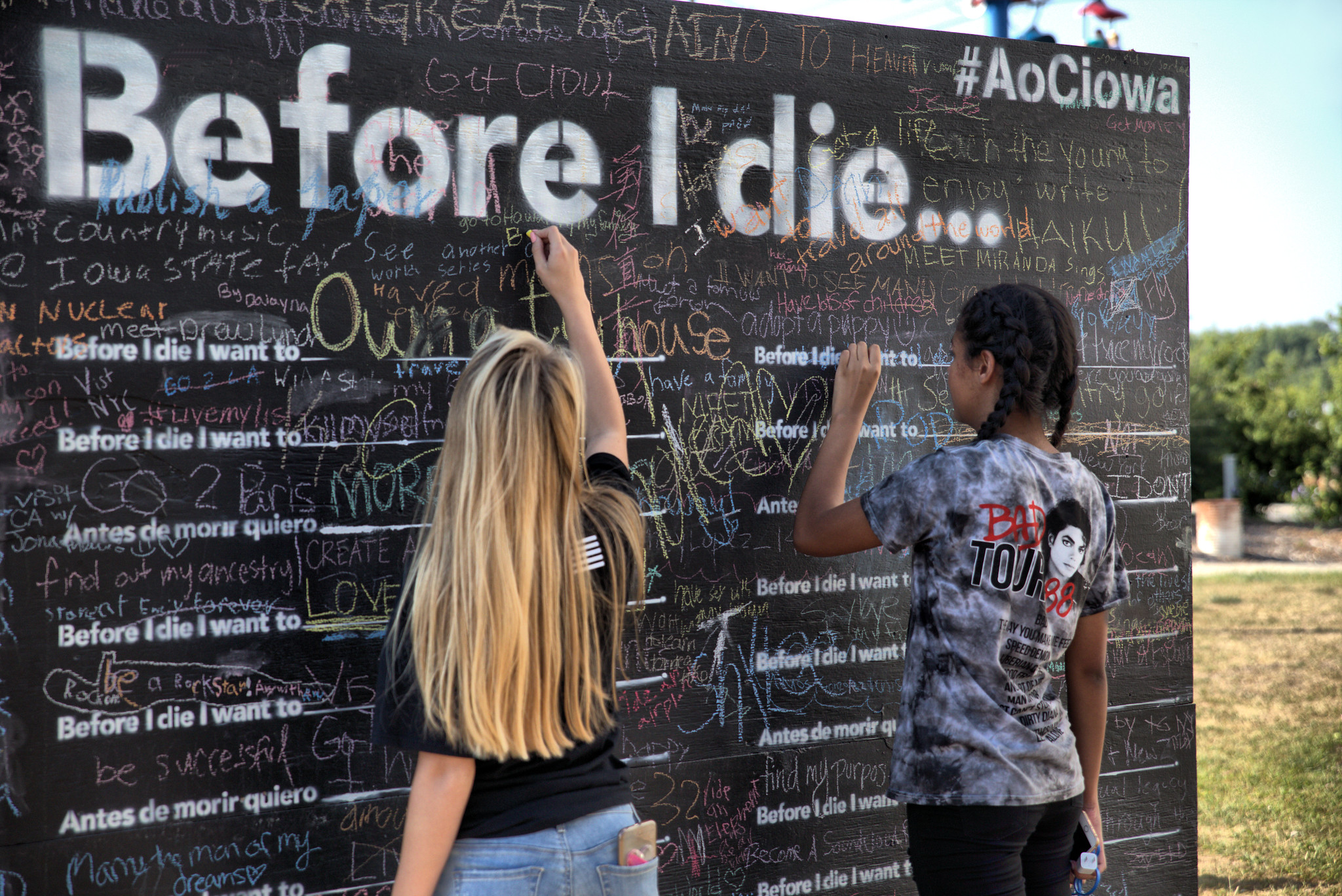

And we have to think about how. They could do TV shows, for example. They could do podcasts. They could do websites. They could do things in front of their buildings. What if all the museums could put a big, long chalkboard and ask, “What’s yours to do?” and let people fill it in?

A Collective Bucketlist. Image by Carol VanHook via Flickr

DL: Is that what you mean by Connecting?

MF: Yes, they would not be doing it alone. That’s the point. Each of these museums is part of a larger network and each of them is a connector that works in three dimensions. They’re connected to their constituents, they’re connected to policymakers, and, most importantly, they’re connected to other organizations. That is the power of institutions.

Photo by David Noles

Photo by David Noles

Mindy Thompson Fullilove, MD, LFAPA, Hon AIA, is a social psychiatrist and professor of urban policy and health at The New School. She has published over 100 scientific papers and eight books. among them Root Shock: How Tearing Up City Neighborhoods Hurts America and What We Can Do About It, and Urban Alchemy: Restoring Joy in America’s Sorted-Out Cities. She is co-author, with Hannah L. F. Cooper, of From Enforcers to Guardians: A public health primer on ending police violence, issued by Johns Hopkins University Press in January 2020. Main Street: How a City’s Heart Connects Us All, was released by New Village Press in September 2020.