#MuseumFromHome

In quick succession, we all had COVID-19 emails pour into our inboxes, notifying us of corporate responses, cancelling/postponing scheduled events, and shuttering venues. The messages bore ominous phrasing like: “As a public health precaution,” “In an effort to further stem the spread,” “In light of the rapidly changing situation,” “Despite such unprecedented uncertainty,” and so on. This dire acknowledgement of the public health crisis also came with invitations to connect via social media and access digital archives. In the following days, listicles started popping up, recommending institutions to follow, art initiatives to check out, and museums to digitally visit around the world, amidst widespread self-isolation.

The pandemic is clearly forcing to the forefront a number of longstanding questions about the online presence and digital tools of museums. Highlighting the importance, variety, and opportunities of such endeavors, this pandemic has also exposed the limits of these tools. Let’s observe what new methods of communication get created as museums test their digital presence and connections. There are a lot of possibilities and some of them are promising.

Now that we all have some extra time on our hands for the foreseeable future, I feel this is the chance to survey some of the best existing examples of recent years, so please also consider this an extended introduction and starting point to exploring institutions digitally that you may have visited IRL.

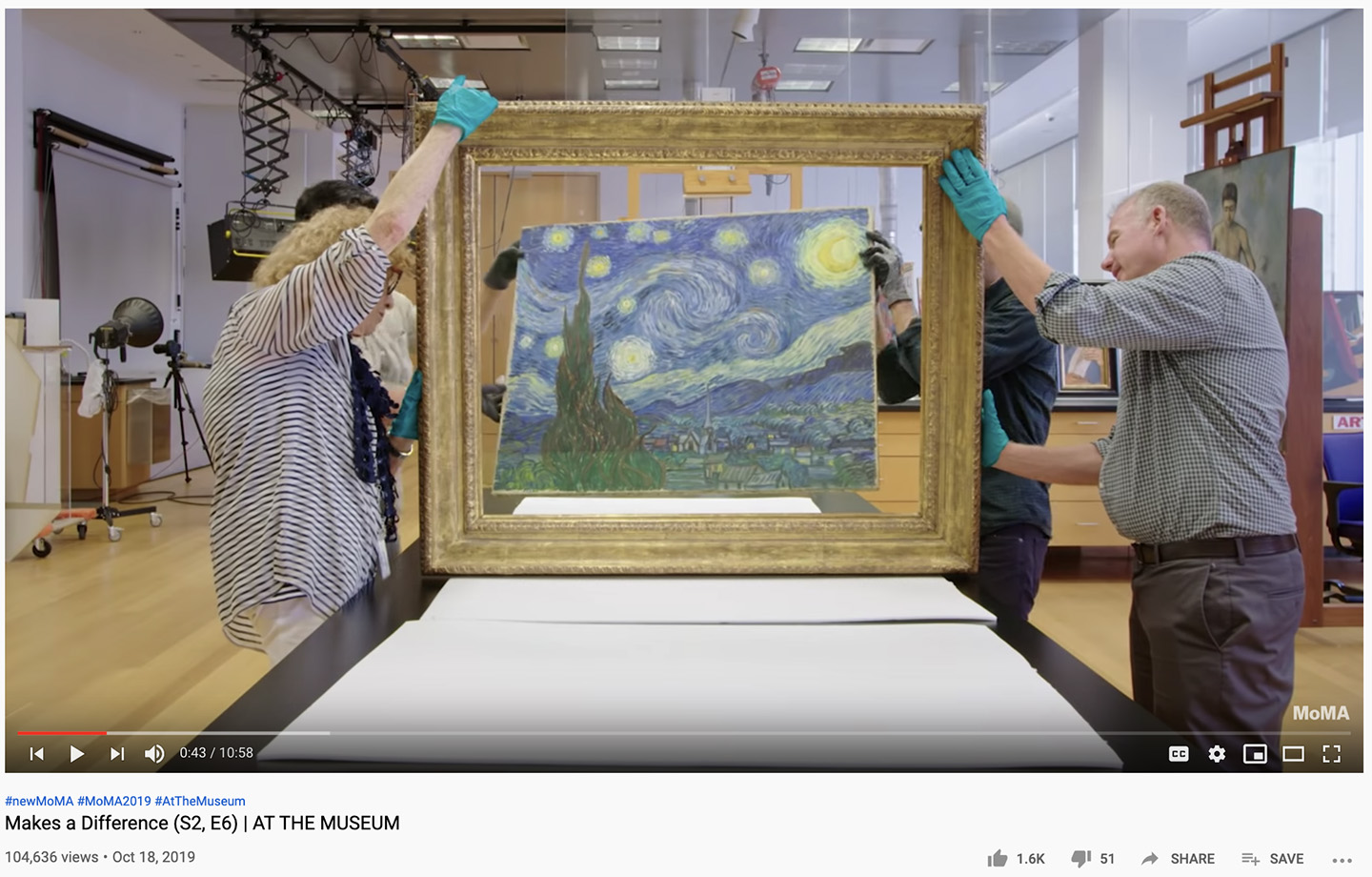

MoMA at the Museum Youtube series, courtesy of MoMA

MoMA at the Museum Youtube series, courtesy of MoMA

Resources for Others, Social-Distanced Media

Reacting to the ripple effects of the virus, many museums, libraries, and universities are aggregating and/or opening up connections to normally restricted resources. From the expansion of databases to on-site usage to the suspension of publisher paywalls, the crisis is hopefully ushering in a more democratic and open-access future for information sharing.

In terms of emergency relief, groups like VisualAIDS or the New School’s Vera List Center for Art and Politics rapidly shared lists and FAQs linking available grants, community care, teaching tools, impact surveys, and food and medication resources. Elsewhere, various museums’ education departments are publishing lesson plans and other materials to assist teachers and parents adjusting to homeschooling. In fact, the Getty Museum’s Coloring Book suits all ages!

There is also an uptick in artists, curators, and administrators developing platforms on social media to mitigate fallout from the massive closures and cancellations. For example, @SocialDistanceGallery is featuring MFA student shows that would otherwise go unseen. As critic Claire Voon at Artnews notes, “In an age when so much art is already being consumed through Instagram, @SocialDistanceGallery is a logical alternative to physical shows. Like many resources born in response to COVID-19, it is also a scrappy and fast-adapting one.” However, shifting to online venues is not entirely without controversy.

In a similar vein to the perennially entertaining/enlightening #AskACurator Day, hashtags like #MuseumFromHome, #MuseumBouquet (flowers), and #MuseumTickTock (clocks) are encouraging institutions to share content, joining in the circulation of lighthearted memes and offering calming contemplative artworks to relieve anxiety-inducing newsfeeds and media diets. As part of #MuseumMomentofZen, the Broad’s post advertising a livestream of a Yayoi Kusama “Infinity Room” registered nearly 175,000 views. Furthermore, museums are increasingly using social media to communicate solidarity and uplift each other. Notable social media initiatives pre- and post-outbreak are inspiring audience creativity, like the Royal Academy of Art’s live-streamed life drawing classes or the Morgan Library’s portrait contest. In the last decade, museums steadily realized the need to devote more attention to online environs and social media channels—the coronavirus is only further expediting such measures.

On social media, the Prado Museum’s unfussy Instagram, featuring commentary by security guards, art handlers, and other staff has proven immensely popular—engaging new technologies, audiences, and voices. In light of the Coronavirus, triage-like responses, such as those undertaken by the National Gallery of Art filming its galleries and impromptu curator talks on an iPhone (like the Prado), exemplify the ways authentic quick-and-dirty methods can function just as well as sleek productions. Discussions around sharing content in absentia might work their way into future disaster planning scenarios, which generally focus solely on safeguarding humans and collections.

In the commercial part of the art world, the online viewing room is emerging as a serviceable arena for sales following the cancellation of art fairs and hiatuses for commercial galleries. Blue chip dealers like Gagosian, Pace, David Zwirner, and Hauser & Wirth have the resources to mount high-quality, information-rich portals, however, smaller galleries will be faced with joining existing platforms and sharing profit margins accordingly. Although retail is moving evermore decisively toward online shopping due to a variety of factors, this format obviously suits some art mediums better than others.

CCA Wattis library, courtesy of CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Art

CCA Wattis library, courtesy of CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Art

Press Pause and Reassess

As museums and broader societal structures develop plans to deal with shutdowns and financial deficits, it is worth reevaluating standard procedures and assumptions, especially when it comes to websites and digital platforms.

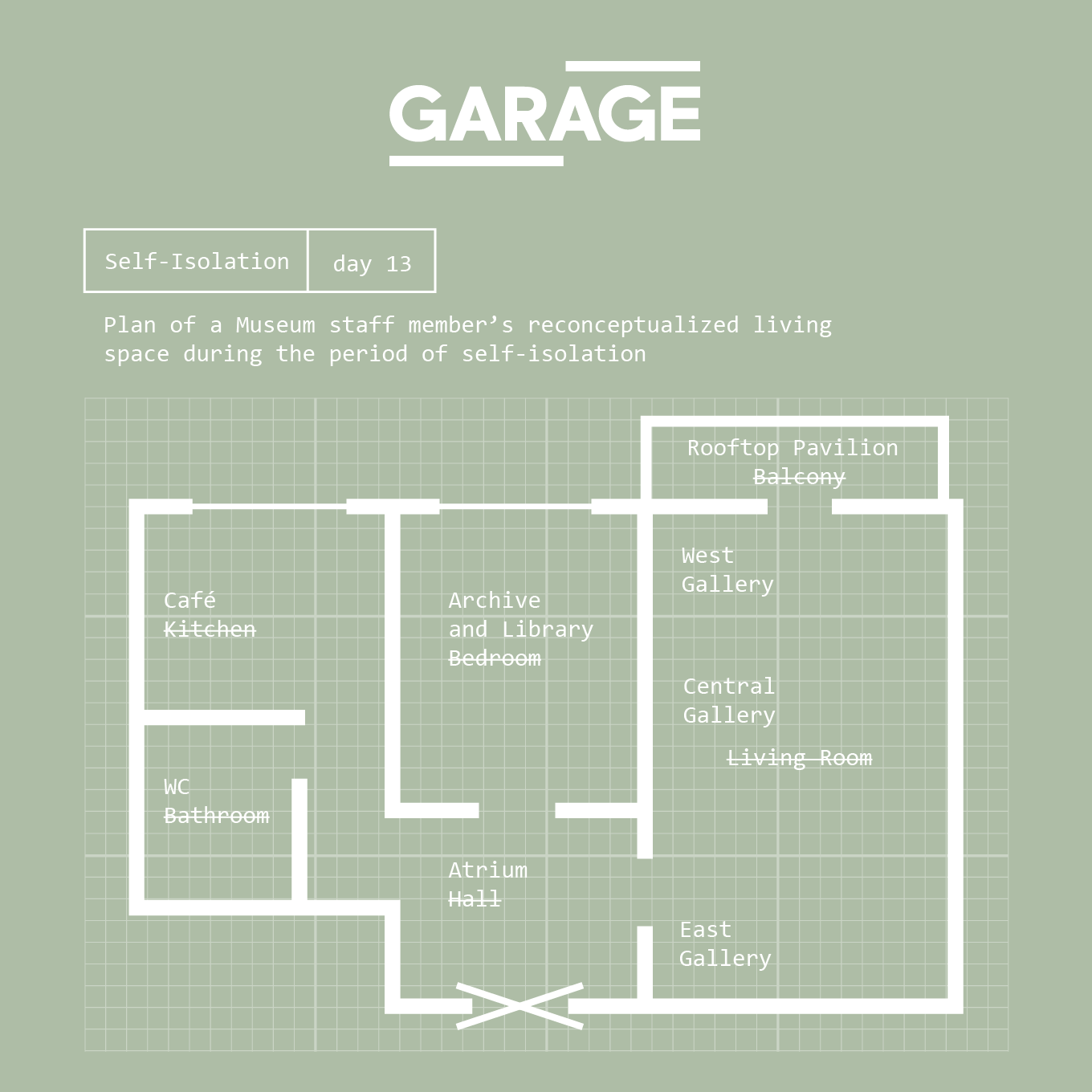

The CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Art, in announcing its new library website of lectures, readings, and essays, explained: “when faced with telling its audience to not visit their exhibitions or attend their events, any art institution finds itself in new territory. We wonder how to remain a public forum for art and ideas that can serve a socially-distanced community.” Innovative examples from the past couple of years might signal new models for others. For instance, the Centre d’Art Conemporain Genève’s 5th floor is a virtual laboratory extending its physical capacity, commissioning artworks specifically for its online forum, adding talks/performances, and operating a streaming radio station. Keep an eye out for the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art’s self-isolation page as another experimental venture.

Garage Museum Self Isolation Mode, courtesy of Garage Museum

Garage Museum Self Isolation Mode, courtesy of Garage Museum

Emergencies often lead to new forms and out-of-the-box thinking; it is impossible to predict how these events will (or will not) reshape social relationships, cultural institutions, and art practices. Indeed, previously unthinkable policies are suddenly on the table and inspiring acts of solidarity and ingenuity are sprouting from this challenging moment.

Bellwether alternative spaces like Performance Space New York and Recess are now asking crucial questions like “how can institutions engage radical care…and [prioritize] access?” and “how do we identify the needs of our community and address them with care?” One concrete step in the digital sphere is an intentional approach to image descriptions and alt text, transforming issues of vision-impaired disability access from mere compliance or afterthought into generative opportunities. Recess advises we slow down and step back together: “Let’s stay close as we distance.” What can we collectively do and imagine moving forward, offline and on?

Beyond reflecting on mission statements, operating budgets, and audience metrics, it would behoove museums to take stock of their digital footprints. A thought experiment and useful exercise considering present circumstances: Let’s hope it will never be the case, but what if none of our beloved art spaces reopen to the public physically and we had to experience them solely on the Internet? How accurately do institutional websites represent their activities, objectives, and ethos? What types of content and tools succeed and why? How does one define and measure user functionality? Where are the areas for improvement and experimentation?

Still have more time on your hands and are you missing your museums? Then let me take you through the best examples of how museums expanded digitally these past years:

Replicating Physical Experiences

A major strand of digital initiatives strives to mimic physical experiences online. The British Library’s user-friendly interface lets readers flip through some of its most popular treasures like the original manuscript for Alice in Wonderland or the notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci and William Blake. The virtual tour is a familiar and effective, if overdetermined, format. Visitors click their way through the (now eerily) empty halls and galleries, looking around, pausing, and zooming in on things that interest them. Interactive 360-degree views provide a comparable visual experience to in-person navigation, allowing an understanding of spatial connections and context. Since 2011, Google Arts & Culture has partnered with 100+ institutions around the world, including the Rijksmuseum, Uffizi Gallery, and Musée d’Orsay, to document holdings. Some are more comprehensive than others, ranging from single galleries to entire floors; likewise, a few museums developed their own versions—for example, the Frick Collection and Rubin Museum’s Tibetan Buddhist Shrine Room both have intuitive interfaces toggling between room and object. The Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History tour has a useful inset map so you don’t get lost. These armchair tours are novel analogs: good to get a sense but not warranting sustained or repeat visits. Perhaps they are not worth the investments of time and money, being unable to capture the myriad reasons and experiences we seek in outings like social interaction. Although remote visits might leave us wanting, there remains great potential in digital storytelling methods to deepen our understanding of cultural artifacts. In general, high-resolution photographs, detailed captions, and in-depth stories of particular artworks encourage close-looking, framing specific details, and introducing narrative commentary or supplemental information, such as a missing Vermeer at the Isabella Stewart Gardener Museum or MoMA’s robust website for Jacob Lawrence’s “Migration Series”.

Uffizi Virtual Tour, courtesy of Uffizi Gallery

Uffizi Virtual Tour, courtesy of Uffizi Gallery

Videos recording docent talks and artist interviews, or ones offering behind-the-scenes glimpses at museum work, are becoming de rigueur practices and audience favorites, at once educational and demystifying. MoMA’s YouTube channel spans exhibition meetings, conservation undertakings, and individual artworks. The British Museum hosts an endearing segment, “Curator’s Corner,” where specialists spotlight personal interests and intriguing objects, from Ancient Egyptian fashion to Japanese manhole covers. For a dose of inspiration, head over to the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art’s “Advice to the Young” series of short videos with wise words from leading artists, architects, writers, and filmmakers. Medium-specific museums are great places to learn more about disciplinary histories and processes, such as the Corning Museum of Glass’s popular demonstrations of glassblowing techniques or the George Eastman Museum’s sequence charting the history of photography.

Many museums are uploading their audio guides, undoubtedly informative yet missing the immediate visual-aural synchrony. Some of the more effective ones involve the artists themselves narrating, like the current exhibitions of painters Peter Saul and Jordan Casteel at the New Museum. Audio content not directly tied to the physical gallery space is particularly successful, like readings of Emily Dickinson’s poetry from the Morgan Library & Museum’s precious show in 2017. Podcasts are also an increasingly popular format, accessible to listeners at their own convenience. One of the best examples is the American Alliance of Museum’s “Museopunks,” with dispatches and accompanying links for further reading on topical issues like virtual reality, decolonization, and self-care. “Museum Way,” by the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, records personal conversations with staff and external guests. Frieze Magazine’s “Bow Down: Women in Art” devotes each episode to a different female artist. Episodes of the International Spy Museum’s “SpyCast” include historians and former CIA agents discussing all things espionage. The Rubin Museum’s guided meditation podcast promotes mindfulness practices to coincide with its exhibitions, certainly a welcome presence in these distressing times. Overall, as with the audio guides, many arts podcasts suffer from the lack of visual material and search for creative ways to compensate.

Digital Collections, Active Audiences

For years, museums have been dedicating available resources to digitizing collections in order to increase wider public access and scholarship. The Cooper Hewitt’s online collection suggests users explore objects and connections via metadata tags like “housing,” “woven,” “colors,” or “sizes.” Similarly, the Prada Foundation just unveiled “Glossary,” harnessing keywords to interrogate its archives. The Minneapolis Institute for Art even offers downloadable 3D scans of collection objects! For non-collecting institutions, publicizing goings-on and institutional histories becomes critical. The New Museum’s archives, launched in 2010 and updated in 2017, stand out as exemplary: the site showcases decades of exhibitions and programs, gathering installation images, printed ephemera, event documentation, and more. Rhizome, the New Museum’s net art affiliate, has long advocated for and set forth best practices regarding born-digital artworks, their preservation, and contemporary display—a tough task owing to obsolete or outdated technologies and software. Artists Space is steadily uploading invaluable content from their archives, encompassing imagery, text, catalogues, and reviews.

MIA downloadable 3D scans, courtesy of The Minneapolis Institute of Art

MIA downloadable 3D scans, courtesy of The Minneapolis Institute of Art

A considered and active online presence is especially important for those regional institutions whose digital visitors equal or outnumber walk-ins. The Walker Art Center and Canadian Centre for Architecture devote substantial attention to documenting and serving up their activities in unconventional ways so as to reach a much larger international audience that might not ever set foot in the physical building. In 2017, MoMA PS1 utilized Twitch, a common platform for streaming video games, to showcase artist Ian Cheng’s machine-learning video simulations, thereby making the exhibition accessible on a variety of personal devices outside the museum’s walls/open hours.

Active audience participation is a promising form of digital experience, welcoming deeper engagement with materials rather than passive consumption. The New York Public Library and National Museum of African American History and Culture both enlist users in novel ways, crowdsourcing transcriptions of collection objects and oral history interviews. In addition to its existing discussion forum, “conversations,” e-flux journal is soliciting readers to become editors, combining an archive of 1000+ articles into new thematic issues. As broad swaths of the world are quarantined, these places are drawing attention to ongoing projects and recruiting the help and intellectual labor of housebound volunteers.

Greg Barton is a researcher and curator focused on spatial politics. He holds a MS in Critical, Curatorial, and Conceptual Practices in Architecture from Columbia University GSAPP and has worked on projects for/with a number of artists, architects, activists, and nonprofit institutions, including the Canadian Centre for Architecture and Storefront for Art and Architecture. His texts have appeared in various places, most recently in The Museum is Not Enough (CCA/Sternberg Press).