Resisting Loneliness with Resilience: Cultural Institutions as Social Infrastructure

I am unhappy doing so many things alone. I have nobody to talk to. I feel as if nobody really understands me. I am no longer close to anyone. There is no one I can turn to. I feel isolated from others.¹

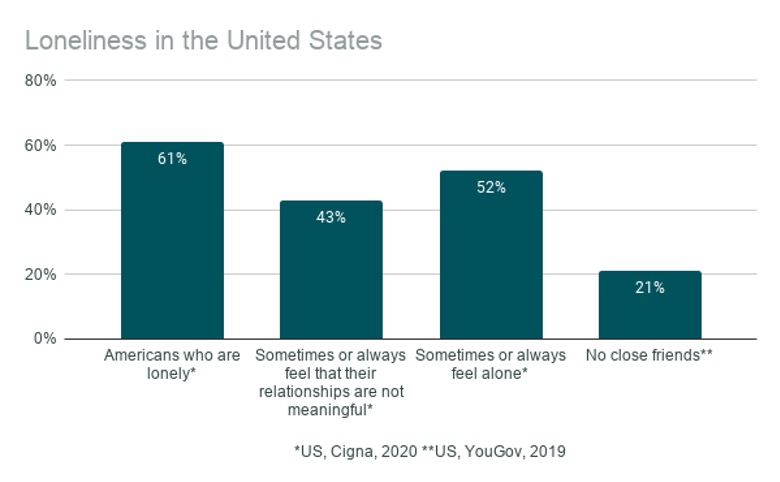

During this moment of unprecedented forced isolation and social distancing, these sentiments likely resonate broadly, but most people are still reluctant to admit feeling lonely. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, loneliness was not only on the rise, it was acknowledged as an epidemic with serious health risks affecting as many as 61% of people in the United States. Even more conservative studies attribute loneliness to 20% of adults, regardless of age or relationship status. Studies show that the impact of loneliness on mortality is equivalent to smoking 15 cigarettes a day. This predisposition is magnified by race; an American Cancer Society study concluded that the most socially isolated Black Americans have double the risk of death. Despite the severity and ubiquity of this public health crisis, the condition is often minimized as a mere personal issue or fleeting feeling. This is, in part, due to the lack of available diagnosis and treatment. Unlike depression and anxiety, feelings of incompleteness, inferiority, alienation, and disconnection that encompass loneliness are often disregarded.

Experts advise that building and maintaining strong personal bonds is the key to countering this epidemic. Community and genuine friendship are sustenance, just as vital as healthy eating and exercise. Cultural institutions have offered—and can continue to provide—spaces and frameworks for true social infrastructure, but first, they need to acknowledge their role in exacerbating the problem.

Image Courtesy of SocialPro

It is important to recognize that merely inviting people into a space does not foster community

Many museums have supported and perpetuated a culture of loneliness in two distinct ways. First, by historically heralding ivory tower prestige, most are unequivocally exclusive spaces. Additionally, the long tradition of championing the achievements of solitary thinkers and makers, reinforces and celebrates the myth that humans are self-sufficient. British historian Fay Bound Alberti draws a parallel between the emergence of the language of loneliness with the culture of individualism. Former United States Surgeon General Vivek H. Murthy, who, in 2017, declared the “epidemic of loneliness,” maintains that the glorification of personal “achievement determined by wealth, power and reputation” leads to feelings of inadequacy, and runs counter to data that demonstrates that we’re all truly interdependent. Beyond shifting programming to showcase collaborative efforts, museums and other cultural institutions can look to social organizations like schools, libraries, farmer’s markets, parks, and community centers as prime examples of spaces that prioritize the well-being of the collective for mutual benefit. As a counterpoint, sociologist and director of NYU’s Institute for Public Knowledge Eric Klinenberg has addressed the damaging effects of an exclusive social infrastructure. He identifies libraries as the “textbook example of social infrastructure in action:” shared spaces that serve as a refuge, nurture intergenerational relationships, and ultimately foster a sense of belonging.

The Art of Gathering: How We Meet and Why It Matters by Priya Parker

There is opportunity and demonstrated success in cultural institutions bringing people together, but it is important to recognize that merely inviting people into a space does not foster community. In her recent book The Art of Gathering: How We Meet and Why it Matters, Priya Parker states that the role of the organizer is “to fuse people, to turn a motley collection of attendees into a tribe.” The goal is to come together with intention, creating expectations and honoring them. This necessitates mutual commitment, which correlates to one great remedy for loneliness: service. Helping others can reaffirm self-worth, counteracting lonely feelings of disconnection and uselessness. Cultural institutions can design opportunities for active engagement, thereby offering a sense of shared purpose.

Feeling comfortable being alone in the presence of others is healthy, and cultural institutions can provide enriching environments where this can be accomplished.

Creating conditions that allow people to feel genuinely welcomed is equally as essential for supporting group connections as it is for individual experiences. Museums have long been spaces where people can be alone together, serving, for some, as a sanctuary for solitary contemplation and engagement. The state of being alone doesn’t in itself indicate loneliness. One can be lonely in a relationship, or feel connected to others while single and living alone. Building the resilience to be truly comfortable with oneself is the ultimate antidote to loneliness. This is possible within a welcoming context that reflects its intended community. Feeling comfortable being alone in the presence of others is healthy, and cultural institutions can provide enriching environments where this can be accomplished.

Image Courtesy of SocialPro

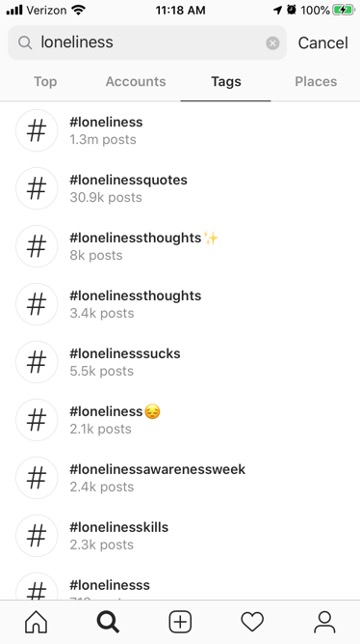

Right now, the global pandemic has indefinitely paused intimate physical gatherings, leading people to turn increasingly to the virtual spaces offered by cultural institutions. Technology gives us more access to each other but doesn’t always ease the feeling of being disconnected. There are several studies on the relationship between technology and loneliness with varying results. Psychologists at the University of Pittsburgh concluded that social media use fuels social isolation, including feelings of being excluded, envy, and the “distorted belief that others lead happier and more successful lives.” While it may be easy to blame Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter for the rise of loneliness, Harvard epidemiologist Jeremy Nobel asserts that social media isn’t “inherently alienating.” These platforms can provide the space and opportunity to normalize and de-stigmatize loneliness. There are currently 7.7M #lonely and 1.3M #loneliness posts on Instagram alone. The ability to share and foster open conversation is key. Openly discussing loneliness allows people to, not only share their feelings and find solace in hearing from others, but also recognize the ubiquity of their feelings.

Loneliness Trends on Instagram, Image via Ashley Mendelsohn

There is a clear need to reinvest in social infrastructure and harness the current climate of change.

It’s not about the technology itself, but how people use it. Using digital platforms purposefully to create and share meaningful personal connections can be restorative. The podcast The Lonely Hour shares stories of the struggles of loneliness but also celebrates the joys of our relationships with ourselves in episodes like The Importance of Doing Nothing and Why Boredom Leads to Creativity. Museums can similarly utilize digital platforms to acknowledge and build shared authority.

It is more important than ever to take loneliness seriously. COVID-19 has exacerbated existing socioeconomic and political divides, underscoring the power and importance of interpersonal relationships. At the same time, the pandemic has demonstrated that it is possible to radically reinvent institutions and infrastructures overnight. There is a clear need to reinvest in social infrastructure and harness the current climate of change. Cultural institutions can elevate empowering forms of gathering that serve as both physical and virtual spaces, where people can discover a greater sense of belonging.

1. Excerpt from the UCLA Loneliness Scale, a questionnaire developed by researchers in the 1970s to measure loneliness

Ashley Mendelsohn is an architecture curator, educator, and strategist focused on engaging and strengthening communities by demystifying the barriers to access and understanding. She previously held positions at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in Curatorial, Exhibition Design and Visitor Experience. During her tenure, she supported the organization and design of Guggenheim Helsinki Now (2015), Åzone Futures Market (2015), Architecture Effects (2018) and Countryside, The Future (2020). Mendelsohn represented the museum during the final stages of the Frank Lloyd Wright building’s UNESCO World Heritage designation process and played a pivotal creative role as the featured voice in the 99% Invisible-produced building audio guide. Mendelsohn holds a master’s degree in design studies from Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design and a bachelor of architecture from Cornell University, and has taught at both institutions. At Harvard, she founded the GSD Kirkland Gallery, which continues to serve as the only student-run gallery on campus. Mendelsohn currently sits on the advisory boards of Madame Architect, a platform celebrating women in architecture, and Impact Wrkshp, an organization that builds community through design advocacy.